At FightMND we call motor neurone disease the Beast. But what is it and how does it affect the body?

What is motor neurone disease (MND)

Understanding motor neurone disease

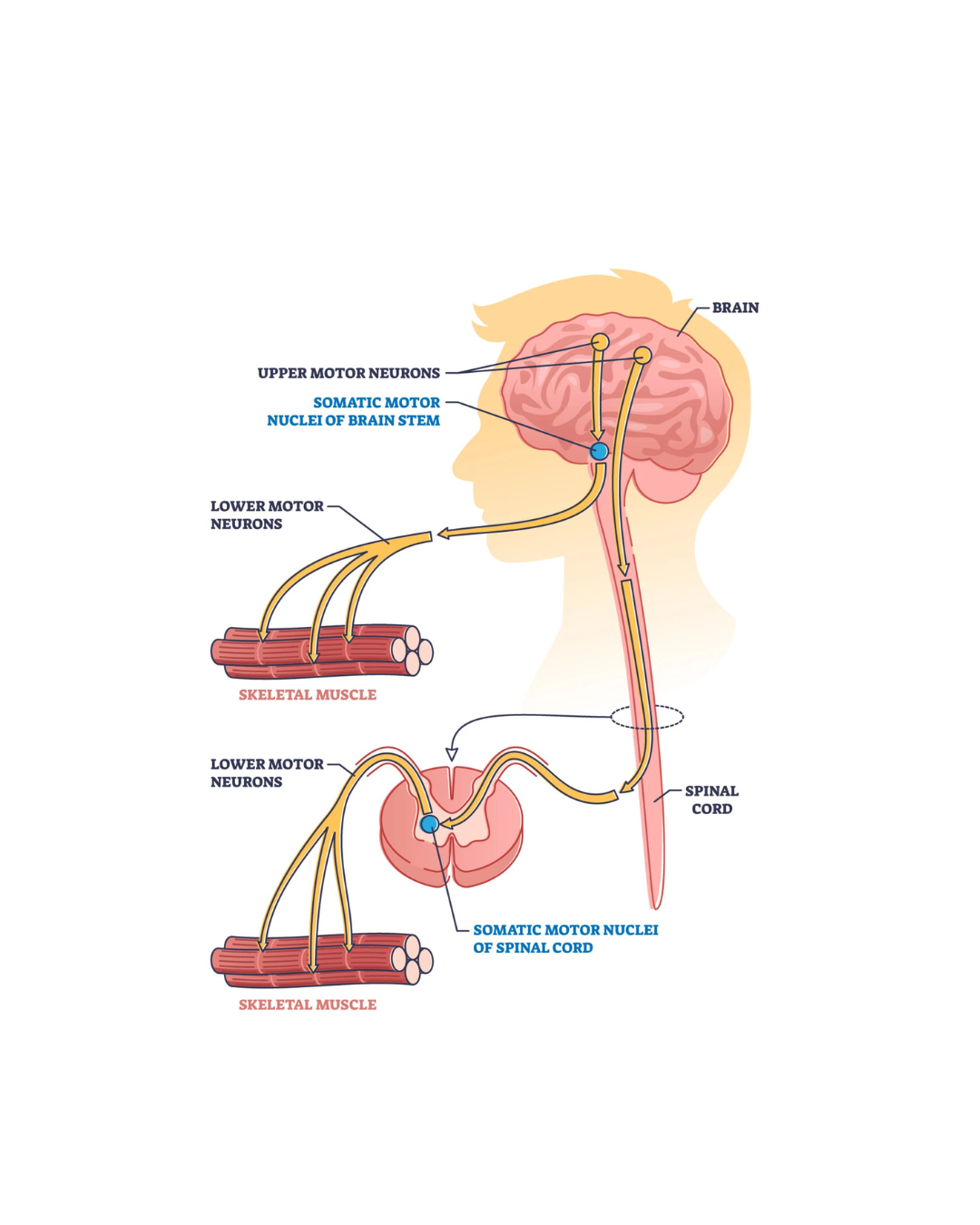

Motor neurone disease, or MND, is the name given to a group of diseases which impact the nerves known as motor neurons. Motor neurons are found in the brain and spinal cord. They send messages to activate the muscles in the body.

With MND, messages from the motor neurons gradually stop reaching the muscles. This causes the muscles to weaken and, eventually, stop working.

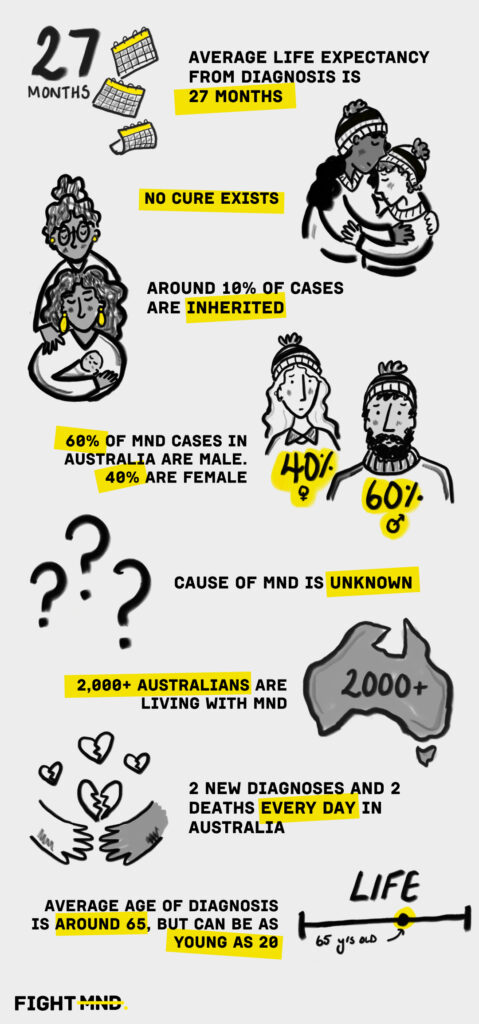

There is currently no cure for MND.

Motor neurone disease is aggressive and relentlessly progressive. While some people can live a long life with MND, the average life expectancy is 27 months from diagnosis.

Motor neurone disease is complex. While we have come a long way, there is so much more to understand about it. From finding its causes to discovering effective treatments. Today we’re at the basecamp of this Everest – and we need your help to reach the summit.

A closer look at MND

Motor neurone disease is also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or Lou Gehrig’s Disease. It is an umbrella term for a group of diseases affecting motor neurons.

There are two main types of motor neurons:

- Upper motor neurons (UMN): nerves in the brain that connect to the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord.

- Lower motor neurons (LMN): nerves in the spinal cord connecting to the upper motor neurons to send signals to activate muscles.

For those living with MND, the motor neurons in their body become damaged and die. With little, or no, motor neurons to activate them, the muscles begin to weaken and waste. Over time, suffers lose the ability to walk, talk, swallow and, breathe.

As MND weakens the muscles, individuals lose the ability to move, eventually becoming immobile. Despite this, most keep their mental clarity even as their physical abilities decline.

There are different types of MND. Classifications are based on the affected motor neurons. Different types of MND can influence the disease’s progression as well as a person’s life expectancy.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

Affects the upper and lower motor neurons. Symptoms commonly start in the arms or legs. The life expectancy for someone diagnosed with ALS is between 2 to 5 years after diagnosis.

Progressive bulbar palsy (PBP) or bulbar onset MND

Affects the upper and lower motor neurons. It affects the muscles controlling breathing, speech and swallowing first. The life expectancy for someone diagnosed with PBP is between 6 months and 3 years.

Progressive muscular atrophy (PMA)

Affects the lower motor neurons. It affects the arms or legs first.

Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS)

Affects the upper motor neurons. It is a slow-progressing form of MND, where life expectancy can be 10 to 20 years or more.

It may take a long time for someone to receive an MND diagnosis. This can be due to:

- similarities of MND to other conditions

- the differences between the types of MND

- the absence of a specific diagnostic test

- the rarity of the disease.

What makes MND hard to treat?

While a lot of progress has been made in the last 10 years, there is still no treatment for MND.

MND is a group of diseases with multiple causes, rather than a single cause. This is why it is so difficult to treat, and why funding research to develop effective treatments and diagnostic tests is so vital.

- There are different forms of MND

Mutations in different genes are linked to some forms of MND.

Around 10% of people diagnosed have inherited a genetic mutation from a family member with MND. This inherited form of MND is known as “familial MND”. The most common gene mutations associated with these inherited forms are SOD1, TDP43, FUS, C9ORF72 and NEK1. It’s important to note that not everyone with a known gene mutation will have MND.

Of people diagnosed with MND, 90% are the only known member in the family to receive a diagnosis. This is known as “sporadic MND”. While there may be a genetic factor, environmental factors may also play a part in the development of MND.

- Environmental risk factors

A combination of genetic mutations and environmental influences play a role in someone developing MND. Environmental risk factors that may be associated with MND include:

- Lifestyle

- Mechanical and/or electrical trauma

- High levels of exercise

- Environmental exposure to chemicals, pesticides, or heavy metals

However, there is no clear link between someone’s lifestyle and environment and the development of MND, and hence not yet possible to suggest ways to reduce the risk of developing MND.

Symptoms of MND

For many patients the onset of MND may be difficult to pinpoint. Many of the earliest signs and symptoms are commonly overlooked or dismissed. Motor neurone disease is diagnosed based on symptoms, medical history and tests to rule out other conditions.

Symptoms may include:

- Muscle twitches, cramps, stiffness or weakness.

- Difficulty with speech, breathing, swallowing or tasks requiring coordination.

- Tripping, stumbling or awkward movement.

While symptoms and rate of disease progression vary between person to person, eventually, due to muscle wasting, individuals will not be able to:

- stand or walk

- use their hands or arms

- get in or out of bed on their own

- swallow and chew

Because cognitive abilities are relatively intact, people with MND are largely aware of their progressive loss of function. This can lead to increased anxiety and depression. Individuals will also lose the ability to breathe on their own and must depend on ventilatory support for survival.

Care and Quality of Life

There is no treatment for MND. But there are ways to manage symptoms and improve the quality of life of someone living with MND.

Medications like Riluzole and Toferson (only for those with a particular genetic mutation) may slow the progression of disease slightly in some cases. Other drugs may be available to manage symptoms such as muscle stiffness, pain or depression.

Multidisciplinary care has been shown to improve the quality of life of a person living with MND, and potentially extending life. A multidisciplinary care team includes a team of health professionals, such as:

- GPs

- neurologists

- nurses

- physiotherapists

- speech therapists

- respiratory physiotherapists

- dietitians

- palliative health care professionals

- social workers and professional carers and more

These professionals work together to deliver care and support to address the complex health needs of a person living with MND.

MND is a devastating condition. Supportive care and early intervention can improve patients’ quality of life and help manage the challenges they face.

More Information

More information about MND is available on MND Connect. For direct care and support for someone living with MND, please visit your relevant MND support organisation website, or obtain a referral to one of the specialist MND clinics from the link below.

What we fight for

The impact of FightMND

FightMND is one of the world’s largest funders of MND research and care projects to support those living with MND . Our investments have increased the number potential drugs to treat MND, and improved access for Australians living with MND to participate in clinical trials, providing hope for those who are currently living with the disease.

Our fight is not over

Motor neurone disease is a Beast. There is no known cure and limited medical care for those living with the disease.

The generosity of our incredible supporters has helped us build a solid research foundation. But we still have more to learn and more to do in this fight.

To do this we need your continued support to help: find an effective treatment or cure for MND, improve the quality, accessibility, and consistency of care for people impacted by MND, and boost awareness of MND.

Your continued support helps us to continue accelerating progress towards finally beating the Beast that is MND.

Contact us

As we continue to fight against the Beast and seek to find a treatment and cure, we would love to hear from you about how you may be able to get involved. Our team are ready to help in anyway they can.