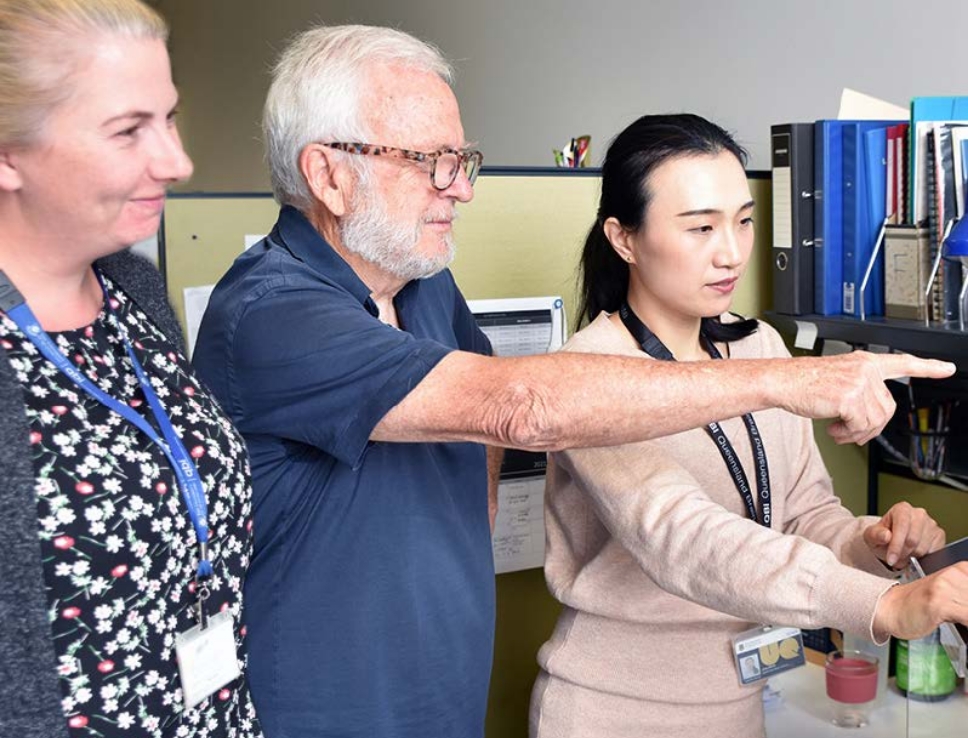

Motor Neurone Disease (MND) is a complex and variable disease, and this can cause challenges in both the lab and the clinic. To better understand the disease, in 2004 a team of clinicians established The Australian MND Registry (AMNDR), a database of clinical data from Australians with MND. One clinician involved in setting up AMNDR was Professor Paul Talman, a neurologist with a specific interest in MND, who talked to us about the registry’s beginnings and how it has changed the MND field.

“The registry began in the late 1990s when fellow neurologist, Associate Professor Susan Mathers and I established a Victorian MND registry based at Calvary Health Care Bethlehem. At that time, we recognised patients presented with different patterns of MND that had very different rates of change and outcomes, and we thought this was important to define as it may help with understanding the disease.”

It was in 2003 when pharmaceutical company Aventis approached Paul at the suggestion of Professor Sir Edward Byrne, a distinguished Australian neuroscientist and founding Director of the Melbourne Neuromuscular Research Unit. The company licenses the only approved therapy for MND in Australia, riluzole. “Aventis wanted to provide an educational grant to enhance the Victorian registry and expand it nationally,” said Paul. Knowing that the registry’s success would depend on the engagement of neurologists and clinics nationwide, Paul and Susan brought together neurologists with a specific interest in MND from around Australia.

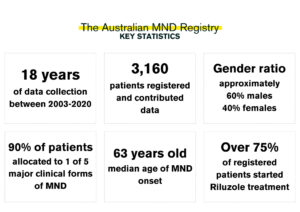

Together, health professionals at participating clinics contributed to AMNDR by recording data from people living with MND who volunteered to take part in the registry. Data was collected on disease milestones, such as the time of symptom onset and symptom progression, to assist with the staging of a patient’s disease. “[The clinics] also collected information on health service utilisation, the diagnostic workup required, and treatments to assist patients with MND.”

What started off as paper-based data entry matured into a web-based platform. “The information was collected by clinic health professionals at each of the state-based MND clinics promoted by MND Australia and the state MND Associations. Data collection and entry was performed as a voluntary contribution by the clinics and is a credit to the health professionals’ dedication in trying to help understand this disease.”

Their main goal was to record how MND evolves in patients within Australia. With the large scale of data collected via the registry, it was hoped that clinicians and researchers would have information available to inform research and clinical care. There were also hopes to assist clinical trial design to increase the potential of successful trial results: “We believed from this beginning [with AMNDR], we would be able to further develop and enhance clinical trials by considering the different disease trajectories that could be defined by data analysis.”

Initially, the data were used to categorise patients based on their symptoms, disease onset, progression, and survival. This helped clinicians when diagnosing new patients with MND, and in identifying the best potential treatment options for each patient.

“The data has also been used by the individual clinics to look at the milestones of their own patient cohort and delivery of care,” Paul said. By looking at disease milestones—for example, when a patient receives non-invasive ventilation (NIV) or a gastrostomy (feeding tube)—clinics have been able to evaluate the care they provide against the best-known standards and continuously work to improve patient outcomes.

“AMNDR has confirmed that forming teams focused on data will enhance care while providing data to external researchers wishing to understand the impact different treatments may have,” Paul said. He notes the work of Professor David Berlowitz (University of Melbourne & Victorian Respiratory Support Service, Austin Hospital) on the use of NIV as one example of how the data and external researchers have helped to transform care for people living with MND. Using data from AMNDR, Professor Berlowitz and his team compared the survival of people with MND who received NIV with those who didn’t, finding that NIV prolongs survival by 13 months. When they compared the data between different forms of MND, patients with ALS-bulbar onset benefited from NIV the most. As a result of these findings, NIV is now offered to most MND patients during their disease.

Many researchers and research initiatives have collaborated with AMNDR, using the clinical data in AMNDR for projects such as the Sporadic ALS Australia-Sporadic Genomics Consortium (SALSA-SGC, with Prof Naomi Wray), induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) program at the Florey Neuroscience Institute (with Prof Brad Turner), and the Victorian Brain Bank (with Prof Catriona McClean).

In 2021, a new registry platform called MiNDAUS (www.mindaus.org) was developed, following a successful NHMRC Partnership grant application, and it now replaces AMNDR. MiNDAUS collects the same registration and type of data, along with the ability for patients to self-register and maintain their own health information which they can consent to share with other health providers and researchers. The MiNDAUS Registry is the new platform linking people living with MND, clinicians and researchers – with the ability to collect the data to answer questions on care, treatments and policy – informed by the MND Community itself.

While data entry into AMNDR has now closed, the registry remains a useful resource for MND researchers and clinicians. “The AMNDR legacy dataset provides information on the natural history of MND and can be used into the future to assess the potential benefits of emerging therapies,” said Paul. “It also provides a dataset to validate new disease staging metrics used to measure disease progression, which will help determine whether emerging therapies are having a beneficial effect.”

Similar to research, the registry depended on funding, which included $150,000 from FightMND over three years. “Throughout its lifetime, AMNDR was funded entirely philanthropically by Sanofi-Aventis, MND Australia, the Pratt Foundation, Wesfarmers, and the Fox Family,” Paul said. “The registry survived on around $650,000 for over 15 years, and while this provided enough money to run the registry, it limited our ability with respect to outputs and the technological development of the registry.”

Despite funding limitations, AMNDR has made a significant impact for clinicians, researchers and, most importantly, people living with MND. Now nearly 20 years on since its national expansion, the registry has helped to change the face of MND research and care in Australia—and it is all thanks to the patients who participated in the registry, and the dedication of the MND clinics, the clinicians involved, external researchers and collaborators.

For Paul, AMNDR’s greatest impacts rest amongst the team it helped to bring together in 2003, and the patients and carers that contributed to the registry: “The greatest outcome has been the network of clinicians that grew from AMNDR, and the sustained development and enhancement of clinics focused on patients with MND and their care within Australia. The generosity of patients and carers in donating precious time has been the cornerstone for the longevity of AMNDR.”

If you or someone you know has MND, and you would like more information on the MiNDAUS registry or would like to register, visit https://www.mindaus.org/